When technology falls out of fashion, it can get lost in history. The trompe is one of those lost technologies. Around the nineteenth century, if a mine were located near a river, they would install a trompe to use energy from the falling water to isothermally compress air. The trompe provided cold, dry, pressurized air to power mining equipment—all without electricity or moving parts. Several trompes still survive, including a 350-feet-deep trompe in Michigan, United States which produce 5,000 horsepower for the accompanying mine, as well as the Ragged Chutes trompe in Ontario, Canada.

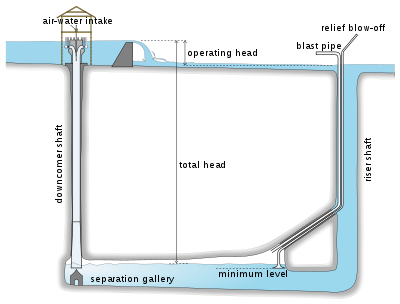

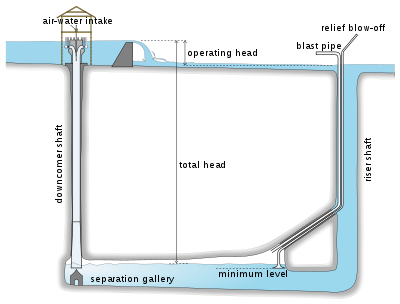

A historical trompe consisted of a vertical shaft, around 300 ft deep, with a conical trough and aeration pipes on top. River water fell through the shaft, dragging down air bubbles through the trough. The shaft traveled to a sealed, underground chamber that held the pressurized air. The water delivered the now-pressurized air to the chamber before returning to the river.

Once installed, a trompe required minimal maintenance and cost next to nothing to operate. It provided cooling and fresh air to the mine workers, and with zero moving parts it was non-intrusive to the river’s aquatic life. However, with the advent of the internal combustion engine, compressed air eventually lost the race against petrol as the popular power supply. By the mid-1900s, the trompe was nearly forgotten.

Now, decades later, researchers have rediscovered the trompe and are investigating how the lost technology could reincorporate with modern techniques. For example, the original trompes were large structures built into the earth, but now we could create a small-scale, portable trompe using PVC pipes. New trompe designs could provide compressed air, aeration for aquatic systems, or refrigeration.

In a modern technological age built on the shoulders of giants, we would do well to revisit our history. Learning about historical technologies teaches us to appreciate how we got here and can help guide us to where we need to go next.